Strange thoughts shape how some people see the world trust feels impossible, even when there’s no reason to doubt. A single remark, meant kindly, can sound like an insult to them, twisting meaning without warning. This isn’t just being careful; it runs deeper than normal wariness. Behind their eyes, everyone carries secrets, each gesture hiding something unseen. Life becomes heavy when every connection seems risky, every friendship loaded with threat. Work suffers, conversations strain, days fill with quiet tension for reasons others never grasp. What looks like stubbornness might be fear wearing a different mask entirely.

This piece looks at PPD its core traits, origins tied to early emotional bonds, frequency, and six clear markers worth noticing. What stands out most is how treatment works. You might be reflecting on your own experience or making sense of someone close to you. Either way, spotting these signals matters. Support exists, and knowing where to start makes a difference. When thoughts twist in unhelpful directions, CBT steps in not by force, but slowly reshaping reactions. New patterns grow through practice, not promises.

Paranoid Personality Disorder Explained?

What sticks out most? A deep wariness toward people, constant doubt woven into daily life. Distrust runs wide, never quite fading. Suspicion shapes how connections are seen. Others feel like threats, even without proof. This isn’t occasional caution it’s unrelenting. The mind leans toward mistrust, again. Seeing motives everywhere becomes routine. That pattern defines it.

Starting off strange, those with PPD often push people away instead of connecting. One thing leads to another mistrust sticks around like smoke after a fire. Testing others becomes routine, almost automatic. Sometimes they feel hunted, convinced someone is plotting against them. Talking openly feels risky, so silence wins every time.

Strange thoughts might link PPD to schizophrenia in conversations, yet they’re separate realities. Though both may share wariness or doubt toward others, one doesn’t drag the other along. Hallucinations and fixed false beliefs dominate schizophrenia those rarely show up in PPD lives. Suspicion walks through both doors, but only one house holds full-blown breaks from reality. People living with PPD usually stay grounded in what’s real, even when trust feels impossible.

The PPD Triad

Picture PPD by focusing on just three main parts

- Suspiciousness – a pervasive distrust of others’ motives

- Grandiosity – an inflated sense of self-importance or being special

- Persecution – believing others are deliberately trying to harm or exploit them

Some feel people around them plan to cause damage on purpose. Others think strangers want to take advantage without warning. A few believe coworkers secretly aim to ruin their lives slowly. Many suspect friends act with hidden bad intentions always. Few trust anyone when danger seems so personal constantly

The Effect on Connections Between People

When suspicion runs deep, forming close bonds becomes tough. People stuck in that loop find it hard to open up, since every motive feels questionable. Trust does not come easily, so connections stay shallow. Without real closeness, loneliness takes root. Growth slows when there is no one to reflect back who you are. Emotions need space to stretch they do better with company.

Causes of Paranoid Personality Disorder?

What lies behind postpartum depression often traces back to childhood. Early bonds shape emotional responses later. Because of this, past ways of connecting matter. How care was given at a young age plays a role. Experiences long ago set certain reactions in motion.

Early Psychological Theories

Out of nowhere, Freud stepped into the world of paranoia, linking distrust and fear of harm to hidden impulses people refused to face. Though his thinking shook things up back then, today’s science leans on proof, not just theory, when explaining such struggles.

The Impact of Early Abuse

In the 1960s, psychologists like Cameron identified that key PPD features, particularly lack of trust, stem from abusive or neglectful childhood environments. An abusive environment doesn’t always mean physical violence. It includes:

- Lack of emotional support, love, and comfort

- Parents who respond with cruelty rather than care

- Being blamed for things that aren’t your fault

- Harsh punishment for normal childhood mistakes

- Being treated less favourably than siblings

- Constant negative labelling (being called arrogant, stubborn, difficult)

Childhood trauma shapes how trust forms

Imagine you’re a child who falls and hurts yourself, but instead of comfort, you’re scolded or hit. Or you tell the truth about something that happened at school, but your parent automatically assumes you’re lying and blames you. When you can’t trust your own parents to support you, how can you trust anyone else?

Children raised in these environments learn that:

- People cannot be trusted

- They must always expect attacks or criticism from others

- It’s safer to withdraw and protect themselves

- Showing vulnerability leads to punishment

Long-Term Impact

Over time, that steady distrust takes root without much notice. Fear of closeness in PPD often grows out of past lessons about staying safe from hurt. A few people start mirroring the strict, domineering actions of their caregivers, turning coldness into a shield – striking first so no one else can get too near.

Here’s what matters most: PPD rarely shows up out of nowhere. More often, it grows from real pain early on, when learning not to trust kept someone safe.

Beck and the Cognitive Model

According to Aaron Beck, the founder of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), individuals with PPD typically have core cognitive schemas that include:

- Feelings of inadequacy

- Poor social skills

- External attribution of blame (blaming others to reduce their own anxiety)

Starting with shaky beliefs can shield someone from facing inner doubts, shifting blame toward people around them rather than looking inward. What feels like defense often masks discomfort too hard to name directly.

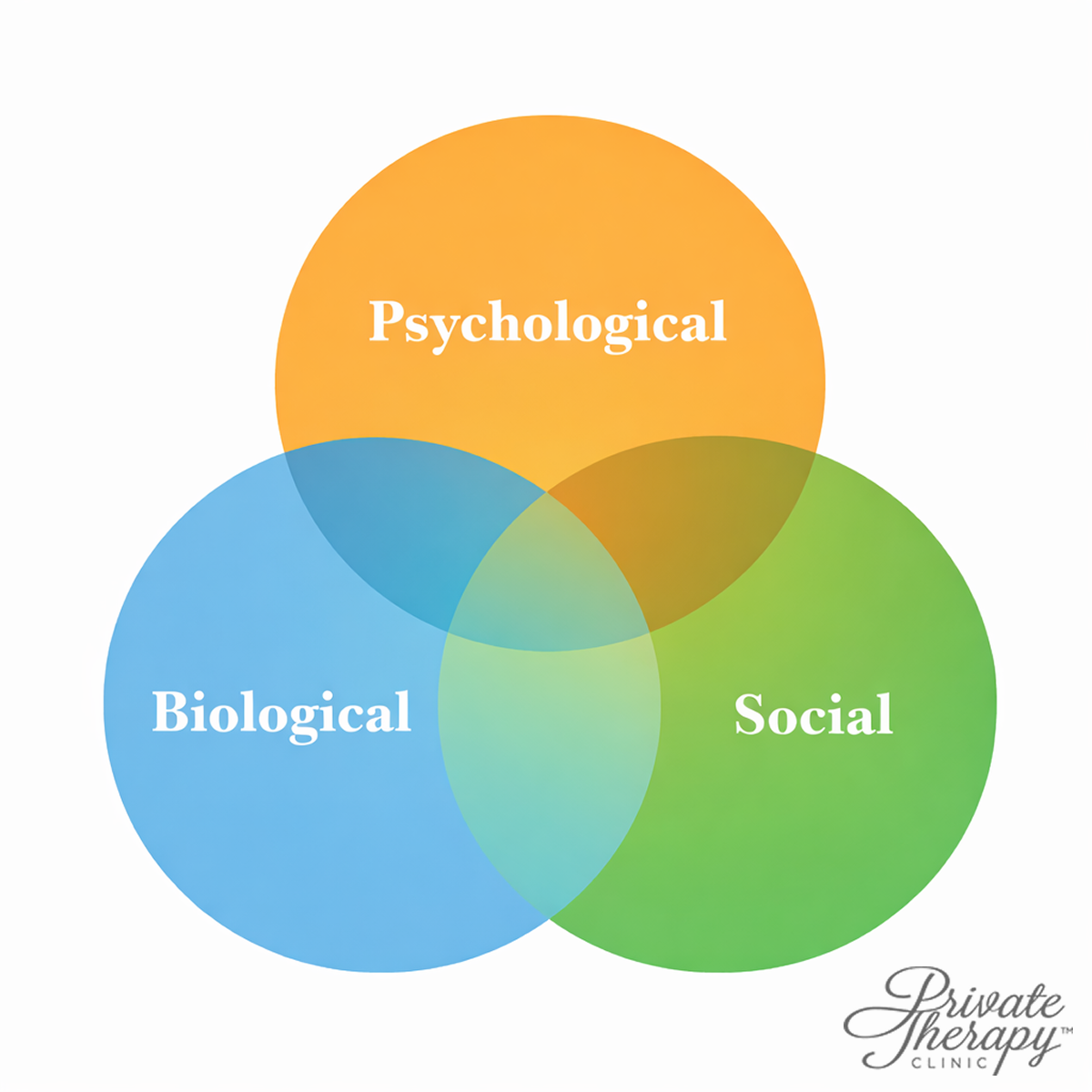

The Biopsychosocial Model

Currently, the most comprehensive explanation for PPD’s development uses the biopsychosocial model, which considers three interconnected factors:

- Biological: Genetic predisposition to the condition

- Social: Early interactions with family, friends, and others during childhood

- Psychological: Individual personality features shaped by environment and experience

Understanding PPD requires considering all three factors together, rather than viewing any single cause in isolation.

How Attachments Show Up in PPD

Pretty early on, those tough moments start shaping how a person connects with caretakers. When kids face rough treatment, trust often gets shaky. Instead of relying on others, they learn to stay guarded. Over time, bonds feel strained, even unsafe. Patterns form that twist closeness into something tense. Without steady comfort, relationships grow uneven. These habits stick – quietly influencing every connection later on.

Fearful Attachment Style

People with PPD typically develop a fearful attachment style characterised by:

- A sense of unworthiness

- Presumption of rejection and mistrust

- Inability to trust their own thoughts and feelings

- Deep mistrust of others’ intentions

It’s common for them to see themselves as unique, set apart from the rest. Guarding their trust becomes second nature, almost like armor built over time.

Childhood Attachment Behaviours

During childhood, these individuals actively avoid their parents rather than seeking comfort from them. They’ve learned to associate their caregivers with cruelty, harshness, and control. Tellingly, they show no preference between a stranger and their parents, indicating a lack of the special bond most children develop with their caregivers. When the people who should provide safety instead provide abuse and judgment, that natural attachment simply doesn’t form.

Adult Relationships

As adults, this pattern continues. Individuals with PPD:

- Avoid emotional investment in social and romantic relationships

- Struggle to open up about their thoughts and feelings

- Maintain emotional distance as a protective mechanism

This chronic inability to form close bonds stems directly from their early attachment trauma, creating a cycle of isolation that reinforces their belief that others cannot be trusted.

Prevalence of PPD

Possibly, men face higher diagnosis rates of PPD compared to women, according to research. Still, that gap might show up because symptoms look different, not because it’s truly more common.

Out of sight, a woman’s struggle might hide behind quiet moments instead of loud ones. Where anger shows fast in some, it slips quietly into mood shifts for others. Diagnosis often catches what shouts, missing what whispers. Seen that way, the difference might not be who suffers more – but what gets noticed.

Treatment for Paranoid Personality Disorder

Most people get help for PPD by talking one-on-one with a therapist. While sharing in groups sounds useful, it often does not work well – worsening things instead.

Individual therapy works better

Out there among others, suspicion often grows stronger. A person might notice sideways glances – wondering if faces hold hidden meanings. Because of that, safety slips away. Thoughts twist toward doubt: maybe these connections aren’t real. Instead of relief, tension builds. Being watched feels certain – even when it isn’t.

Goals of Therapy

The main therapeutic goals include:

- Building trust in the therapeutic relationship

- Developing positive relationships with others

- Opening up emotionally

- Reducing learned aggressive or cruel behaviours

The Therapeutic Relationship

Patience matters when trust grows around a person living with PPD. At first, therapists face doubts just like any other stranger does. Doing exactly what was promised – over days, weeks – begins to shift how they’re seen. Steady actions speak louder than words, showing safety without announcing it. Slowly, those moments add up, loosening the grip of second guessing.

This journey moves at its own pace, yet small steps still count. Sticking with it matters more than speed, because waiting quietly often brings change.

The Role of Medication in Treating PPD

Medication plays a small part when it comes to handling PPD – its effects are tangled, unclear. Right now, not one drug stands out as reliably helpful for this particular condition, simply because the illness doesn’t follow predictable patterns.

Problems in Medicine Studies

Finding good medicine solutions isn’t easy – each hurdle shapes the outcome differently. One obstacle follows another, yet progress stalls regardless. Problems pile up, still answers stay out of reach. Every attempt faces new resistance, even when methods seem solid at first glance

- A tenth of those dealing with PPD actually reach out for help, which leaves studies short on info

- People often hold back from pills when doubt takes root. Mistrust colors their view of treatment. Hesitation grows where belief falters. Medication feels risky if motives seem unclear. Wary minds question what they’re offered. Uncertainty blocks routine steps. Fear hides behind quiet refusals. Doses go unused when trust is thin

- It’s often difficult to distinguish between personality traits and co-occurring conditions like depression or anxiety

Medications That Could Be Helpful

Even so, some medicines might ease problems

- Mood stabilisers: Prescribed to reduce aggressiveness and impulsivity

- Fear fades a bit when Prozac enters the picture, fluoxetine working quietly behind the scenes. Aggression dips – not gone, just softer around the edges. Suspicion loosens its grip, like a hand slowly opening after holding too tight for too long

Here’s something worth keeping in mind – drugs often target particular signs, not the core issues tied to personality disorders. A psychiatrist needs to handle prescribing and tracking those medications, weaving them into a broader strategy built around counseling.

Thinking About Paranoid Personality Disorder

Starting early in life, often shaped by painful experiences, Paranoid Personality Disorder grows from deep wariness passed through years of guarded living. Though constant suspicion and pulling away from others make daily life tough, healing remains possible. Therapy that moves slowly, stays steady – especially one-on-one methods such as cognitive behavioral techniques – opens space for change. Trust begins to form again, thinking shifts from rigid to more flexible, connections grow stronger when support holds firm over time.

Finding out what causes PPD – how early bonds form, how biology and environment mix – shows these actions come not from choice but survival, shaped by real harm in childhood. Healing can happen when help fits the need.

Further Reading

Curious about personality disorders? Try reading Daniel Fox’s book called The Clinician’s Guide to Diagnosis and Treatment of Personality Disorders. Though it dives deep into PPD, it also explores many related conditions. With solid research behind each chapter, the guide outlines how professionals identify symptoms, then follow up with practical care strategies.

Get Professional Support

If you’re struggling with the issues described here, please get in touch. At The Private Therapy Clinic, we offer a range of services including Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) to help address symptoms of PPD and related conditions. We also offer ADHD and autism assessments.